Edinburgh Art Festival: Platform 2023

Edinburgh Art Festival's Platform exhibition returns with a fresh cohort of emerging talent. This year, each artist has been paired with a writer from the EAF x The Skinny writer programme to explore their practice

Rudy Kanhye

A word in the title of a previous project by Rudy Kanhye captures my attention. ‘Goni’, meaning gunny, both in Morisien (Mauritian Creole) and in my native language spoken in the south-western coast of India, resonates with a history of transoceanic travel, passage, trade and the intermingling of cultures across the Indian Ocean and beyond. This particular history of indentured labour goes back to between the early 1800s until 1920, when European nations instituted the transportation of people largely from India after the abolition of slavery in 1833. These people worked on the sugarcane plantations of Mauritius and elsewhere as cheap substitutes.

The small island nation of Mauritius is situated to the east of Africa and has undergone a long history of occupation and colonisation by the Arabs, the Portuguese, the Dutch, the French and the British, until gaining independence in 1968. As a result, the society today is a mixed group of people coming from diverse cultures and geographies, practising various food systems and speaking different languages, but identifying as Creole. Kanhye supposes that his ancestors came from the northern region of India – traces of this memory are retained not in family records, but in the intangible flavours of a homeland, contributing to the tangible food cultures passed down through generations.

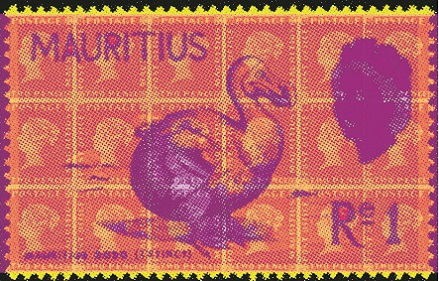

Rudy Kanhye, Dodo-Raphus-cucullatus. Credit: Rudy Kanhye.

References to Mauritius and what was historically branded as its ‘Coolie’ cultures is central to Kanhye’s research and practice. He employs storytelling, engages in archival histories and facilitates conversations around food through community-sharing as approaches to decolonising the art space. As part of Platform, Kanhye will be showcasing his project within the premises of a church – a space for quiet contemplation. Titled Don't be scared of Red, Yellow, Green, Blue (a reference to the colours on the Mauritian flag) the showcase will include a large digitally-printed banner of eyes encompassing the wall outside – indicating a feeling of being watched. Inside the church, two framed digital prints of historical Mauritian stamps will be displayed, embellished with the portrait of the British queen alongside the image of the dodo – the national bird of Mauritius. The dodo’s extinction in the late 1600s serves as a reminder of the violent consequences of colonialism on native ecologies.

The last day of the festival will witness Kanhye’s food participatory performance entitled Composition of Red and Yellow – the red symbolising a past of struggle, and the yellow of the sun a hope for a better future. The artist will be cooking and serving a vegan meal of red and yellow curries to visitors, in memory of the coconut fish curry he relished with his family on the beach at the age of eight – the taste of the sea, the sand, the heat, the smoke, the spices, the community. [Shalmali Shetty]

Crystal Bennes

In her playful condensing of 17th-century Irish history, artist and researcher Crystal Bennes will foreground colonial histories and gendered labour for Platform this year. Through an array of materials and objects – including linen, a milking stool, and rolls of lawn – the installation combines domesticity with graft, upending the spatial separation of living and working.

On the morning I speak to Bennes, her afternoon plans sound messy and engrossing in equal parts. Weeks before the opening of Platform, Bennes divulges her continued search for a dairy product to sculpt a bust of the English political economist William Petty (1623-1687), the figurehead of her installation. Out of respect to the three other contributing artists, as well as the visitors, she has been on the hunt for an ingredient which won’t degrade into a rancid pool during the three-week exhibition run. She found that butter was a "pain in the arse" to work with, although it would have been the ideal material to communicate her meticulous research into Petty and his perpetration of English colonialism in Ireland. Contrastingly, Bennes welcomes degradation to the lawn, as it naturally wilts on display. Inspired by a passage in Lars Iyer’s novel Wittgenstein Jr., the lawn’s deterioration speaks to the satirisation of Englishness as neat, constricted, and controlled.

Opting for slow and careful archival research to shape her artistic output, Bennes integrates text into her installation to communicate the complexity of the issues she confronts. In the British Library, she came across a paper disturbingly titled About Exchanging Women. Inside, Petty sets out a proposal to 'civilise' Irish Catholic women through ‘transmutation’. Noting that Petty employs alchemical language, Bennes describes how Petty believed that 'civilization' could be achieved by shipping poor Protestant English women to Ireland and marrying them off to Catholic men. In this way, Bennes observes that the proposal rendered the women oppressed but also as ‘agents’ of Petty’s colonialism. Contemporarily, 17th-century Ireland saw a rigorous expansion of its butter industry which was not without socio-political tensions. For Bennes, the significance of the butter is a "material connection with women’s domestic labour." While she has resorted to milk in the end (because of its stable properties), the dairy-based bust will grant 17th-century Irish women a "small revenge against Petty by rendering him in the fruits of their labour."

Bennes’ contribution to Platform has been years in the making, simmering since her PhD on the culture of the sciences, yet continuously sprouting into unconventional and provocative directions. For exhibition purposes, her art-making has sped up. The passage of time, symbolised through disparate, decaying materials like grass and dairy, figures so consciously in her installation. [Rachel Ashenden]

Aqsa Arif

For Platform, Aqsa Arif will exhibit a film, the screen set within an architectural façade inspired by South Asian folk stories and the pre-colonial architecture of the Heera Mandi. The central film work captures a traditional Indian dancer as she reinterprets South Asian folk tales. Arif is specifically influenced by The Seven Queens of Sindh, the story of the Suhni Mehar, and the archetype of the moral woman who sacrifices herself in many South Asian folktales. She has also been researching the profession of the Tawaif during the Mughal Empire – once an elite role for women, but one which has since lost much of its value due to the imposition of colonial moralities. She implores viewers to confront difficult questions surrounding culture, identity, race, and colonialism. These complex central themes may make some viewers uncomfortable, while providing a source of empowerment and validation for others. Arif is acutely aware of this powerful dichotomy, and relishes the fact that her work will elicit a divided response.

Asqa Arif, Spicy Pink Tea. Credit: Aqsa Arif.

The work is ambitious and confrontational, requiring that the viewer enter a bounded physical space, unable to escape difficult questions surrounding history, culture, colonialism and identity. Arif’s desire to unravel her own sense of self and relationship to her dual Scottish/Pakistani heritage manifests itself in her interdisciplinary practice – she encourages us not to think in singularities, but rather to understand that our identities and psyches are composed of various, disparate threads. In particular, Arif is committed to understanding her own identity and embracing its complexities, irregularities and confusions through her interdisciplinary practice.

Arif notes that many of her inspirations are film-based, ranging from exquisitely colourful, often kitsch, Bollywood music videos to the installation films of Pipilotti Rist and the digital art of Ed Atkins. Cinema takes a front seat in Arif’s artistic approach, however it is always displayed with a variety of other mediums. There is no escape in the cinema. Depending on your inclination, that is both a comforting and unsettling thought. We sit in a darkened room, with nothing to distract us from the moving image. Manipulated by the filmmaker, we are suspended in a dreamlike space. In relation to her installation for Platform, Arif has created an architectural space audiences will enter to view her film. They will be immersed, their normal environment temporarily on hold, existing in a new realm drawn from a pre-colonial past. [Maisie Wills]

Richard Maguire

This summer, Richard Maguire will show a series of drawings and objects as part of Platform: 2023, Edinburgh Art Festival’s Early Career Artist Award. The work builds on research into Peggy Hall, a child sent to Scotland from India alongside an enslaved woman (perhaps her mother), who was then ‘returned’ to India, as she was considered by the British government to be an ‘illegal object’.

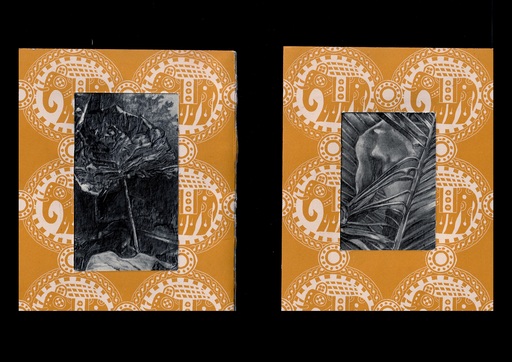

What is so magnetic about Maguire’s practice is his interest in materiality – particularly in his drawings depicting photographs from various archives. Each of the drawings layer two photographs together with the effect of double exposure, creating more detail and more content, and simultaneously less clarity. Where the edges of the neat frame and mount are sharp and clean, the line work and material effect of the graphite is fluid and undefined. These aspects of Maguire’s works speak to the obscurity faced when engaging with misunderstood histories: indeed, he found it very difficult to find concrete information on the life of Peggy Hall, whose records were destroyed in a fire.

Richard Maguire, not everything fades away. Credit: Richard Maguire.

Peggy’s story will also be present in the objects on display at Platform: imagined recreations of her jewellery that were recorded in a shipping log. Through these objects, Maguire thinks about people’s status as objects, but also what objects Peggy herself may have owned. Jewellery plays a huge part in South Asian matrilineal heritage, and it is where a woman might find autonomy through those objects passed down from her mother. Placed next to the drawings and their commentary on hidden histories, the shining physical presence of the jewellery will add a visible and tangible weight to Peggy and her story: seen and felt and found in the room.

Maguire cannot (and does not try to) totally resolve Peggy’s pain or repair a heavy history of colonialism, but he does offer a gesture of repair and healing: an effort to see Peggy and her intimate reality. Archives can easily be active acts of colonial othering: information is hard to find, and people are spoken about in callous numerical terms of their inventory or monetary worth. But Maguire’s intervention of the archive brings emotion, intimacy and warmth to how we engage with history and its people. Time and colonial erasure might stand in the way of us knowing each other fully, but Maguire’s work brings us a little bit closer. [Laura Baliman]

Platform: Early Career Artist Award 2023, Trinity Apse, 11-27 Aug, 10am-5pm