Transient Edinburgh

Can the festival city serve its creative communities year-round? We look at Edinburgh's relationship with the arts, the fringe, and its various communities

Edinburgh is labelled as the ‘world's leading festival city’ due to the various cross-cultural events such as the Fringe, Edinburgh International Book Festival, Edinburgh International Festival, and Edinburgh Art Festival all happening simultaneously across the month of August. As such, the city is well known for its showcase of arts and culture, but what happens after August has been and gone? What and who is left in Edinburgh?

With over 12% of the city’s population being students (according to the 2011 census), and with 4 million visitors each year in contrast to a population of 524,000, Edinburgh is a city constantly in flux; a city of arrivals and departures. Having built an identity on tourism, the city is largely shaped for those who have experienced it for only a short time, with an understandably romanticised perspective of an energetic and creative Edinburgh in response. The danger of this transient experience is that Edinburgh may itself become lost in upholding an identity as a tourist and student city, while issues related to its local community become obscured from view.

I am wondering how sustainable the August festival model is in relation to having a concentrated period of time which is bustling with people and creativity, only for the same energy not to be upheld throughout the rest of the year. Of course, there are other smaller yet still very exciting festivals that happen in Edinburgh such as Fringe of Colour Films, Spit it Out, and LeithLate, which take place at different points across the year, and it is not to say that a wider community of creatives doing interesting things does not exist within the city. But what I would like to see is an investment in Edinburgh’s artistic community that is also visible and supported throughout the year, as opposed to only one month which mainly serves an international audience. There are a multitude of issues with the Fringe itself – who it is for, who it excludes, and the financial costs associated with it, but I would also like for us to extend these questions to critically consider the current lack of commitment to the arts and artists themselves who live and work in Edinburgh.

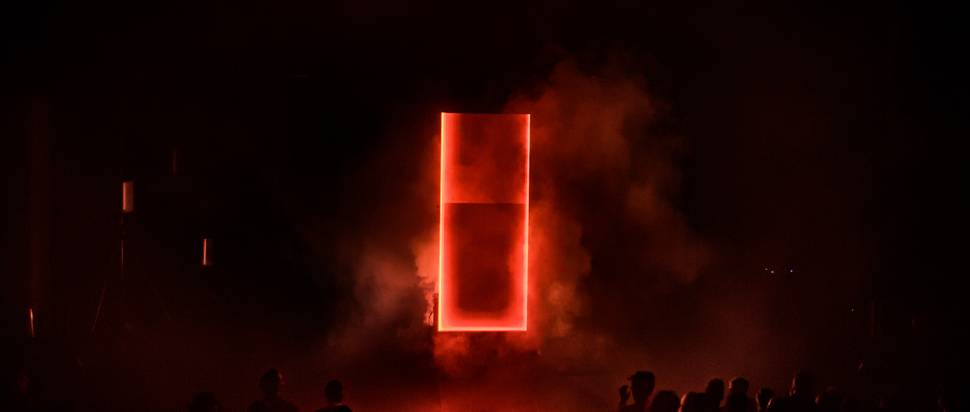

Haven for Artists at French Institute, Edinburgh Art Festival. Credit: Myriam Boulos.

In recent years, we have seen important cultural spaces shut down, such as the artist-run gallery and affordable studio provision Rhubaba Gallery & Studios in 2021, and the independent nightclub Studio 24 in 2017. Spaces are being closed as a result of property expansion in the case of Rhubaba, and noise complaints for Studio 24. This is a contrast to the seemingly 'creative city' which Edinburgh has claimed as its title. As seen through the closure of these spaces which were integral to builiding creative communities, the reality is that the value of arts and its community is not entirely being upheld beyond August. This is further noted through the increasing rent prices and lack of opportunities for artists, which sees regular movement of people to more affordable and vibrant cities like Dundee or Glasgow, especially for their contributions to contemporary art and live music. These cities have established many more independent spaces for exhibitions, gigs and events, something which is hard (but not impossible) to achieve in Edinburgh due to the increasing living costs, plus the lack of available physical space for creative enterprises to take over due to the constant demolition and building which serves to increase the student accommodation all over the city.

How might Edinburgh operate in real time? Perhaps by building on the current relationship that the city has with tourists and students to include investment in existing communities. There have been talks to introduce a Tourism Tax, which has been seen in other tourist hotspots such as Venice, in the hopes of supporting a more localised approach to tourism. This will hopefully see funds be used to improve services and public spaces in the city all year round, including for residents. This initiative could be expanded to invest back into communities and cultural spaces which serve the communities who are not always visible – who operate outside the August festivals, and who may be facing issues of precarity which come with the increasing unsustainability of working within the arts.

A critical approach to thinking about festivals and tourism is integral for creating a mindful approach to how we might engage with different forms of culture. Sometimes I wonder who the city is for, and what its relationship to art might look like in years to come. I hope to see a visible dialogue between Edinburgh and its communities, with the future-proofing of cultural spaces and creative people firmly placed within its landscape.

This article was produced as part of Diverse Critics, a talent development programme for disabled and/or Black and people of colour arts writers delivered in partnership between Disability Arts Online and The Skinny and supported by The National Lottery through Creative Scotland