Infinite Loop: Tako Taal on her expansive new exhibition

We meet Tako Taal to learn more about about her expansive DCA solo exhibition, At the shore, everything touches

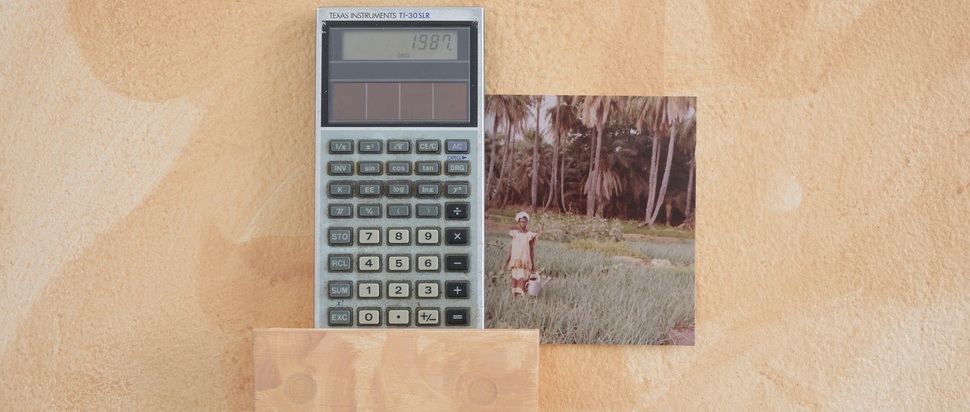

Some objects are carefully arranged on the wall by the entrance of Glasgow-based artist Tako Taal’s solo exhibition at DCA, At the shore, everything touches. These include four photos, a newspaper clipping in a polypocket, a detailed drawing of a chair, and an old calculator that reads ‘1987’. The objects were the belongings of Taal's father Seedy Taal, who died in 1990. “All the documents [were] collected after his death then passed on to me, some at a very early age then others more recently.”

Taal’s father’s works and belongings form one important basis for Taal to consider the changing nature of Juffureh, her family’s home village in The Gambia. Historically a trade post and fort during the transatlantic slave trade, the island is also near Kunta Kinteh Island, named after the central protagonist in Alex Haley’s 1976 bestselling novel Roots: a young man taken from The Gambia when he was 17, and sold into slavery. Roots also tells the story of seven generations of Kunta Kinteh’s descendants.

Since the release of the book and the hugely popular film adaptations from the 1970s, there has been a touristic interest in Juffureh and at one point in the 33 minute film work SAMT utterance_01 (how a name becomes a step, a rhythm, a loop), a tour guide leads a small crowd who walk from one side of the frame to the other, as the camera films the mainly white group from a fixed position and at a distance. There seems to be a patient observation by Taal of the visitors, who form part of – as described in the press release – an “ethically complex tourist industry”.

I ask Taal how she balances the competing demands of publicity and privacy when making an exhibition that pivots on items of close personal significance. “That question has basically been what I've been trying to understand by making this work. I think about what someone when I did a residency in Dakar said: what goes in the work? What is just for you, and what goes alongside it? Those three categories of what is present in the work, what is alongside and what I’ve kept have been essential in how I’ve been working with this material.”

Even with this clear framework in mind, initial plans for the exhibition and the works nevertheless changed in ways that surprised Taal. “Maybe it’s useful to say how I haven’t worked with it [the collection of documents passed down from her father to Taal]", she says while laughing at the strange inversion of this approach. “I always thought about using the poems that my dad had written as a script of this video piece. When I first started thinking about it, that’s how I imagined it and when I was shooting the footage, these quite long landscape shots: I imagined this voiceover going with them. That’s why you have these formal, long durational shots. I tried to work with them in that way, but they were just very difficult to edit essentially, and the language is so particular. Also you can see that they’re still first drafts; they have little notations and corrections in them, so they are unfinished in themselves.”

Throughout At the shore, everything touches, there are aspects of the installation that push at the expectation of its easy categorisation as a solo show that everything must be singly authored by the artist herself. “It was really important for me in making this work that it wasn’t just my voice in there and I think it’s something about the way in which I’ve gone about the research for this project and I’ve encountered many other ways of thinking about this place.” The writing and photos of Taal’s father are one example of this, but there are also two artworks by the photographer Maud Sulter. “The works by Maud Sulter were a surprise for me," says Taal. "I wasn’t familiar with them when I started to conceive this project and when I was filming in the project. I only encountered them on my return when I was looking through the Passion catalogue [for the 2015 exhibition of the same name in Street Level Photoworks, in Glasgow].”

The images that Taal includes in the exhibition come from Sulter’s photographic essay, Sphinx. To quote Sulter herself, the photos document “the shipping posts of slavery days. Tiny islands off the coast of West Africa where in a handful of sand one can still uncover beads torn from our bodies before an internment which culminated in transportation by ship.” When all nine photos were first exhibited, they were accompanied by Sulter’s words: ‘Only the wailing of the women remained.’ The phrase appears again in Taal’s SAMT utterance_01 (how a name becomes a step, a rhythm, a loop).

In the exhibition, Sulter’s two photos face Taal’s two screens, setting up a literal parallel between the two artists’ works. At one point, Taal includes a near identical shot in the film work, initially shot without being aware of Sulter’s photographs. Taal describes a feeling of a powerful moment of recognition, upon seeing Sulter’s photos for the first time. “I had literally been standing in that spot, and knew exactly where the shot had been taken from. There was something about the visual of it and that very embodied memory of a place that I got from looking at the photographs that really surprised me.

"For me, at that point I was also thinking about what it is to make work about my family and things that are intimate and personal, and there are ways that I understood – as the title suggests, where everything touches or where these things intersect, how these narratives of diaspora and transatlantic slavery and colonialism all hit on other aspects of life both historically and in the present.” Taal felt a rapport, “similar thinking that had gone on” about “the importance of these sites, and how they connected with someone visually in quite a formal way.” Taal says: “They encouraged me that these have a much broader interest.”

Throughout the exhibition, there are recurrences and relationships between the physical materials, the filmwork and the audio elements. The structure of the film as three 11-minute loops comes from the length of the infinite tape’s duration. There are two watercolour paintings, which Taal sized to 16:9 ratio to be the same dimensions of the film screen, but at an intimate scale. While there are separate parts to the show, they are brought into contact with one another in surprising ways. At first, Taal decided to divide the space into a light then a dark area, but this division was not so clearcut.

“As I was installing, I really understood how much they rely on each other, and there is something about the sound [composed by Claude Nouk in collaboration with Taal, and playing alongside the film in the dark space] that I think really plays quite an integral part to the reading of the wall-based works [in the brighter space, that audiences first enter].” When I visit, the sound work created by Claude Nouk creates a complex audio space, that among its many complicated textures at one point thumps as from below the ground, then becomes an immersive hum, layered and dimensional. Sometimes, the sound suggests the strikes of an excavation, at other points the engine-drone of a journey: a boat, a car, a bus, a plane.

Taal describes the ways that the materials repeat between the different spaces, too. In the light space, audiences are invited to spend as long as they want with the documents, the wool embroidered cloth, the facsimiles of Taal’s father’s poetry. In the video, they quickly flash on the screen, demanding a more energetic kind of looking to identify the action and detail of the images or scanned items. “What I wanted to tease out were these different ways of being with things: these more rooted and immersive glimpses, the intensity of encountering these things in the video work. Then there’s a – for me anyway – a quietness, and there’s a study and contemplation you can have with the paintings and the gold chain for example, or with the photographs of the installation, or with this piece of fabric.”

The film was edited to the rhythm of the 11-minute loop time that came from the technology of the infinite cassette tapes, and working with this predefined time limit was new to Taal. ‘The video work is conceived as a loop, it is three 11-minute sections that form a continuous loop and it’s conceived as such that it could be added to. That loop comes from the 11-minute duration of the infinite tape and so we had to create precise work around this arbitrary timing. This was a new process of editing to me as it had this very formal structure. Because of the way I wanted it to loop, I kept having to think about ways it could potentially be felt differently [than having a conventional beginning and end on a linear timeline].”

I bring up an interview when Taal had previously said, “I really enjoy embracing the collapsing of time.” Speaking about this interest as it appears in the current film work in At the shore, everything touches, Taal says, “through the process of looping there was a collapsing of the experience of time, so the experience in the exhibition – I hope – is that you could walk in at any point and be aware that it is happening, that maybe you have entered at a specific point but you might not understand where the beginning and end are, and all you are aware of are these repetitions. You are aware of the cycle rather than the beginning and the end: the line.”

At the shore, everything touches, Dundee Contemporary Arts, until 20 Mar

dca.org.uk/whats-on/event/tako-taal