Fresh Fruit of the Loom: Tapestry Makers Talk

We've woven together interviews with 21 tapestry makers to bring some insight into what it means to work with a medium that's often more associated with antiques than contemporary art

In the Era of the All-Media Artist, when an Adobe Creative Suite subscription is more important than a studio, it’s with some surprise that this month brings two separate tapestry group shows to Edinburgh. One is in the City Art Centre, opening in the middle of this month; the other already open in Inverleith House, the Cordis Prize 2021.

In a time when virtual artworks can fetch dizzying sums sold via hi-tech non-fungible tokens, Cordis Prize shortlister Zhanna Petrenko asks, now that so much “is digitised, what value can the tangible object have? Galleries are becoming online platforms, artists are communicating and making experiences with each other less and less… [literally] quarantined all over the world.” Petrenko’s own work is a response to the ongoing military action in the South of Ukraine. She uses images that for her draw attention to the “information warfare in the media,” using tapestry to make “the pixels disappear.”

With relatively few chances to see tapestry IRL, there might be some misconceptions about what goes into making one. Joanne Soroka, who is exhibiting in the City Art Centre explains: “What we do is tapestry weaving. A lot of people who talk about 'tapestry', it’s actually embroidery they’re talking about.” The latter being the kind of work made using 'tapestry kits'. With these, people stitch along according to a guide on top of an existing textile, sewing threads into it to make an image, "whereas what we do starts from scratch.” On this point, see also Maija Fox’s Cordis entry, a 3D woven sculpture using traditional Finnish textile weaving techniques and hand stitching, repurposing techniques usually used in making hardy snow-socks.

If this sounds time-consuming, it’s because it absolutely is. But as Sara Brennan (in the City Art Centre show) explains, after decades of working with tapestry, “you can do things that you can’t do with any other medium… Wool absorbs the light. It makes for a different kind of black compared to painting, which makes a reflective surface.” Fellow Cordis exhibitor Fiona Rutherford, whose tapestries resemble gestural hand-drawn marks, picks up this point with regards to her work. “It wouldn’t work as strong as a painting. The depth of colour and the texture would be absent.”

The unique woollen black is also mentioned by Katja Beckman, whose Cordis work is indeed a black monochrome rectangle in portrait orientation. It’s also covered “in thin rya [threads] knotted in and hanging from the woven fabric. Rya has a unique quality to create a living surface. It has an inviting effect, you want to get close and touch it.”

As well as allowing for visual impact and presence that other media can’t reproduce, Patrick Stratton from the Cordis shortlist assures that the process is also “supremely addictive.” For him, despite its long and somewhat illustrious history, tapestry is still a mostly untapped medium in terms of the potential that still exists within it. “It isn’t material dependant, it’s just a process of making a form of fabric. Anything can be woven really! Dog leads, bank statements, maybe even scaffolding. That’s what I think it can offer contemporary art, along with a rich history of making.”

Tapping straight into this history, Chrissie Freeth is the most classically-inspired maker. While Freeth’s tapestries are close interpretations of Medieval works (speaking to her other life as an archaeologist) they delicately subvert existing antique forms of the medium. For instance as a “play on medieval hunting tapestries” and as a response to the self-reflection many had no choice but to engage in over lockdown, Freeth shows a stylised landscape and set of characters, one of whom is looking for their own likeness. Instead of a deer or boar, “it is the self that is being sought.”

In contrast, across both shows there are artists – like Jo McDonald, Angela Maddock, Fiona Hutchison and Susan Mowatt – who put their tapestry training to work, but use materials that wouldn’t have been envisioned by Medieval makers of “portable wallpaper”, as Cordis exhibitor Martin Nannestad Jørgensen describes the classical use of tapestry. Once upon a time, they were moved around the stone walls of towers to keep the inhabitants from catching a draught. Instead, for the kinds of experimental weavers on show, works are made using paper streamers, repurposed plastic packaging, or torn-out pages from books.

Somewhat reminiscent of Sheila Hicks’ heftily piled floor-based textile works, Angela Maddock’s Cordis entry work is a meditation on absence, isolation and loss, made from second-hand garments that have been carefully sliced apart then “reassembled here through knotting and weaving. … Shoulder to shoulder, hip to hip, thigh to thigh...” Her work contains, among other things, leggings, pants, pyjamas and sweatshirts, no fewer than 96 T-shirts all “otherwise destined for the ragpile.”

While some artists bring materials into their tapestries that aren’t classically used, Cordis exhibitor Anne Bjørn pushes at the expectations of what a tapestry can hold by incorporating hi-tech processes into her making process, as she uses laser cutting to create a grid, which is then woven with paper yarn. They blow up the usually imperceptible kinds of connections and knots that make up a tapestry. Similarly, Patrick Stratton pushes at the lo-fi associations of tapestry. His woven and cartoonish looking illustrations of mundane daily activities – as a twist – include kinetic, motorised elements, making the images literally move.

While material experimentation and technological additions are some ways of bringing the show up to date, contemporary social issues are the motor behind the works by Cordis shortlist artists Anna Olsson and Nakahiro Misako. Through making portraits from selfies of friends in the asylum process, Olsson attempts to confer some of the status of tapestry to people that have been refused institutional recognition and so denied the means for their own survival. She breaks the mould of the dawn-til-dusk weaver, as her time is split between her work in textiles and as a psychologist for young people fleeing persecution, seeking refuge in Sweden.

For Nakahiro Misako, based in Japan, it was the raft of new visual forms of COVID social regulation that became her inspiration for her Cordis submission. Her tapestry could be a distorted Op Art work, neon yellow and white stripes melting out of alignment, looking like a sheet of hazard stripes reflected in a funhouse mirror. “I created this work during such a chaotic time. Yellow is often used as a colour of caution. I wove this picture of stubborn stripes distorting as a symbol of hope in a world where [new rules are everywhere].” Speaking of the slowness of image-making that tapestry represents, Misako sums up: “There are things that only become clear when the time is taken to understand them.”

As much as tapestry might take a lot of time, for all its regal associations, the amount of tech needed to make an impressively scaled work isn’t as outrageous as might be expected. Elaine Wilson describes being furloughed from her tapestry weaving apprenticeship at the start of 2020, and how she furnished herself with what she needed to make her first independently woven tapestry. "I didn’t have my own loom at home, or any materials required for tapestry weaving; so I ordered an industrial clothing rail to warp up and use as a loom, and a selection of wool so I could get to work.” A trained painter, Wilson’s tapestry is a technically complicated abstract titled Blue Splash, representing thrown and dripping paint using tapestry techniques.

In City Art Centre, there is inclusion of works by artists like Tessa Lynch, Gordon Brennan and Henny Burnett whose common denominator is their departure from an early training in Tapestry. This allows certain aspects of tapestry-making to be shown to cross over to other media. Take Henny Burnett’s 365 Days of Plastic. Burnett slowly accumulated her own plastic waste, and cast it dedicatedly in pink dental plaster throughout the year. Lines of association emerge between her methodology and the iterative and patient build-up of a tapestry.

Or take Tessa Lynch’s Handhelds, smaller scale aluminium sculptures, “based on buildings in plan that I moved through on my commute, then I made them into perforated net type shapes.” Lynch mentions as one potential parallel to the tapestry process, the “very methodical [and] mathematical way of making them.”

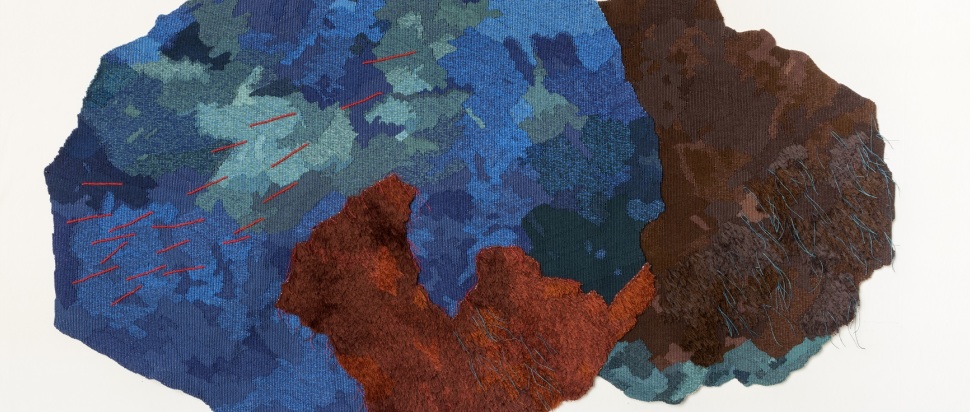

Gordon Brennan’s works on show are the latest in his materially experimental practice which extends several decades back to his seven-year apprenticeship in Dovecot Studios. When he went to study in ECA, he applied principles of tapestry to casting and sculpture, namely that the work doesn’t need a “backdrop” and instead – as Joanne Soroka already mentions above – “the form, the surface and the colour is all cast into one thing.” In his exhibited work, he shows some of his experiments with works that have a base and skin, but also perforations that allow the wall to be seen behind. He suggests in a way this makes for a shared characteristic with tapestry, “which is draped, it’s not flat,” namely that “you’re aware of the wall behind.”

To finish, a note of caution on tapestry from Cordis award winner and City Art Centre exhibitor Susan Mowatt. “It can produce pretty bogging, horrible stuff. Lots of people seem to think if they spent three months making them, it’s somehow valuable.” It’s a useful dousing of the infectious enthusiasm that comes from interviewing 21 tapestry-makers. But it’s still just a medium like any other, with just enough exceptional and era-defying examples to act as reminders that stunning visuals don’t always need a high-powered server attached.

The 2021 Cordis Prize for Tapestry, Inverleith House, Edinburgh, until 12 Dec

Tapestry: Changing Concepts, City Art Centre, Edinburgh, 13 Nov-13 Mar 2022

Inline image: 'Rest' (2020) by Gordon Brennan, image courtesy of the artist