GSA Degree Show: The Beat Goes On

After a tumultuous year at Glasgow School of Art, its final year students pull focus back to vanguard art practice and the cultural life of the city

With over 150 students' work, the undeniable star of the Glasgow School of Art degree show is the recently purchased Stow Building. The refurbished college has kept its original tiles and generously tall windows, and is stunning in both rain and sunshine, both of which are seen looking into the courtyard in the centre of the structure. The Stow will provide new studios for all future Fine Art disciplines, bringing the departments together for the first time in 50 years, proving that there will be life post-Mackintosh.

On the ground floor, Colm Guo-Lin Peare’s work contrasts human with computer recognition. Immediately apparent are digital videos of a monolithic face, a Hong Kong city scape, and a recorded voice. A gallery-style wall text stands between the works, banally offering explanation. Reading this text, however, confounds understanding and the works recede from recognition. We are told we are looking at the output of artificial intelligence. While there are moments of humour – the similarity of the nonsense art-speak text to derivative theory; the simulated face belongs to noted curator Hans Ulrich Obrist – this belies a disturbing suggestion. We have lost the ability to tell what is real. As we make our way upstairs, Marguritte Carson’s business cards on Floor 1 offer something to fiddle with throughout the rest of the exhibition.

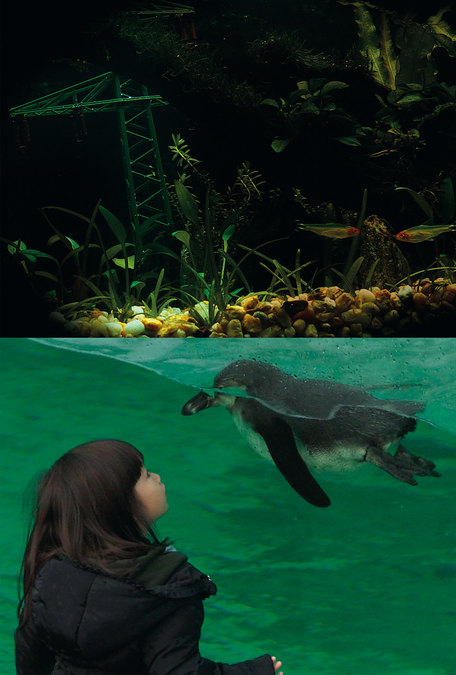

Another one of the video works that stood out is by Finn Rabbitt Dove, whose work reflects the high-level of professionalism that is shown throughout the show. Titled Films You Watch When You're Ill, it is an ode to bad television which, as illustrated by the nostalgic tones of Windows96 and ESPRIT's soundtrack, already seems like something of the past. The work recreates the feeling of falling into the box wrapped in a blanket through its voyeuristic shots of gazing subjects – the old at paintings, the young at aquariums – as you gaze at the TV mounted impressively on the brick wall.

Also on the first floor is Kate Lingard, whose space is filled with casts created from structures of the inner ear as well as recreated videos of what looks like empty hallways. The accompanying text perfectly illustrates the work without over-explaining it; it is a highly successful work in itself. The text is often the most ridiculed part of a degree show, but this shows a strong proficiency, reminiscent of queer-feminist literary theorist Maggie Nelson in its union of clear intellect and unashamed emotion.

Martha Horn’s work has a similarly poetic feeling to it. Two Girls Trying depicts two girls singing on the stage of the empty and slightly dilapidated Kings Theatre. The film focuses on the vocal warm ups and the characteristically female overly-apologetic missteps. Displayed on two screens, both performances run into the other, developing a relationship as they serenade each other whilst simultaneously drowning the other out. This is, ultimately, a romantic piece, belting cheesy love songs to one of Glasgow’s oldest theatres.

Reflected throughout the show is the strong influence of Glasgow as a city upon the students and their artwork. This synergy is particularly reflected by the recurring references to club culture, both through its music and queer communities. Performance artist and Drag Ogre, Shrek 666 (the current resident performer at queer club night SHOOT YOUR SHOT) has already accomplished a lot outside the walls of GSA. Sorcha Clelland’s alter-ego was inspired by Dreamworks' Shrek, a character forced into isolation from the community that was afraid of him. Through creating this character Clelland explores the parallels between queerness and horror. Artist Ivy Deacon’s work shares a similar exploration of camp and fandom, featuring ceramic cow boy hats and a soundtrack featuring Madonna and The Cure among others.

Music is a recurring theme throughout the Degree Show with synths and drum machines blaring on every floor. One successful example is Billie Angel, presenting a series of recordings created by inviting other musicians to collaborate with them on tracks created inside their bedroom. This engaging work aims to “produce an international album of tracks which will re-engage global friendships”. Listen out for their collaboration with Ross Sinclair in particular.

The club sounds selected by Heidi Chiu are pushed to distortion; they burn through double sets of fire doors. This work, physically set apart, announces itself. Yet on entering the room audiences are met with a seeming contradiction. A sweet scent blends with the yellow light coming through the vinyl-tinted windows. Cushions lay on the floor. Were it quiet, this would be a tranquil space. We are implored to rest and notice the names on the walls. They are barely visible having been painted over in white. As viewers we are attracted, as listeners we are repelled.

The message is clear and the volume is unbearable. This work asks what the conditions for tranquility, rest and peace are, and who controls them. The title, They know that we know we can fight this, poses the transhistorical questions – Who are they?; Who are we? and What is the fight? Even with the added complication of Silicon Valley, our 21st Century answers look much the same as those of the 20th.

Louis Nye’s, Io Worthington’s and Jack McGarrity’s work is strong and compliments each other well, providing a welcome break on the third floor of this five-floored show. It's not clear why the degree show is over five floors of the building, as only two floors fill up even half their space. Perhaps they wanted to show off the entirety of the building, or perhaps to exercise the audience? The most likely rationale seems to be Health and Safety reasons, nevertheless you feel extremely sympathetic towards the artists on the uppermost floors who are clearly at a significant disadvantage.

Although as expected there is not a shortage of work exploring the digital world, nature and the anthropocene more often takes centre stage this year. Separate students claim collaboration with both the sea and an apple tree for their final show. The student whose work manages to perfectly balance sincerity with humour is Toby Mills, who presented lovingly reared eels and a mock-Attenborough film focussing on a bird morgue.

Throughout the Degree Show there is the usual and ever-present atmosphere of competition. Countless stickers litter the walls, some of which look like they could even have been printed off that morning. An opportunity to discuss these issues and other topics comes at the event Common Ground, self-organised by students of Glasgow School of Art as an “informal discursive event aiming to explore and question the degree show context”. Unfortunately, too often this is an event that is built towards and then quickly forgotten, and certainly this year's Degree Show has work worth remembering.