Envisioning a Theatre For All

Looking into a new year, this month's writer pulls back the curtain on shallow diversity schemes in theatre – and points to new roots from which he and all can thrive

It’s 2065 and the global majority no longer feel minoritised. The bigwigs have woken up to discover that white people can stomach Black and brown stories on stage. Having plenty of people of colour in power certainly helps. We’ve stopped asking if the straights are okay because they now regularly see gay lives on stage and are better off for it. Audiences and creatives alike revel together in a radical new reality where theatre isn’t for 'theatre folk'. It’s as popular as the movies again. It speaks to all. As a breadth of worldviews regularly reach the biggest audiences, theatre finally grasps what it has always strived for: truths that reflect our world.

'Diversity' has been on an odyssey in recent years, thanks to the tireless work of many minoritised people and our allies. But we all know the fight is far from over. We need regular rallying cries to take stock and energise ourselves for the next leap. We’re seeing more diverse casting, but for high-profile productions, 'progress' looks like Black Juliet on the West End – which still draws a not insignificant amount of bigoted vitriol. The reality for actors of the global majority is that we’re still commonly afforded race-doesn’t-matter roles written for white people, especially once we emerge from the grassroots seeking a sustainable professional career. The chance to tell our own stories? Well, they’re surely too niche for mainstream audiences.

Except we, the so-called 'ethnic minorities' make up a fast-growing 13 percent of Scotland’s population. We are the mainstream too. And when global majority narratives do get big platforms (Dark Noon, Ryan Calais Cameron’s For Black Boys Who…) they can attract large audiences and rave reviews. Part of the problem is that the global majority are not making up the audiences, or the people in power. To start, we need intentional intersectional diversity in leadership, in artistic directors, programmers, and CEOs of funding bodies, so broader worldviews are deciding which stories are platformed. When the vast majority of Edinburgh Fringe attendees are white, and only one person of colour leads a theatre in Scotland (by Engender’s latest report), it’s clear the issue is both institutional and cultural. Hiring strategies alone won’t dismantle an industry built on blackface, gross stereotyping, and narrative erasure. We have to pick apart the whole structure. Anti-racist and progressive culture must be cultivated widely, so the responsibility isn’t left to our new leaders to hold the burden of change-making.

In Scotland, we are seeing a diversity bottleneck in theatre. At the grassroots level, we meet many queer, women, global majority and otherwise minoritised performers. At the Edinburgh Fringe, which attracts many independent and international theatremakers, I can fill my personal watchlist with excellent stories centring minoritised lives; I still have to work hard to find these stories, though. Fringe of Colour calculates a mere seven per cent of shows centring people of colour – hardly representational for a group we call the global majority. And at the bigger theatres year-round, I can’t find nearly the same diversity. Funds and schemes for global majority creatives receive fleeting support, can’t sustain themselves and mostly target the early-career levels. We’re calling for diversification of the system, but don’t have sustainable support streams to allow people from diverse backgrounds – especially low socioeconomic backgrounds – to rise up. Diversity is being funnelled out at higher levels, and the stories that do make it out risk being flattened for the market, or co-opted by those in power who influence how they can be presented.

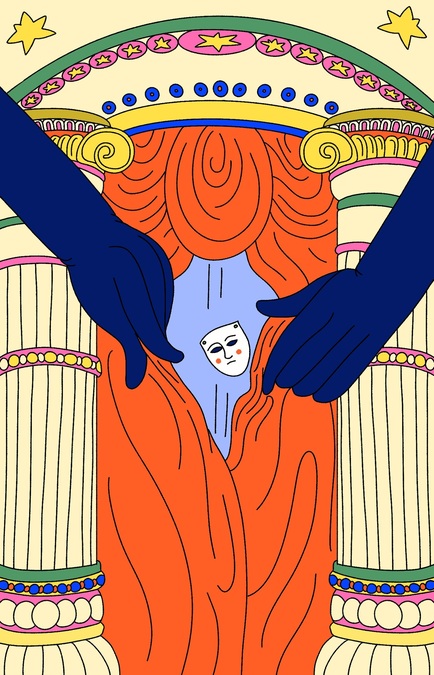

Illustration by Viki Mladenovski

Whiteness and a middle class sensibility are currently the twin tickets to thriving carefree in Scotland’s theatre culture, but this hasn’t always been the way. We’ve shaken our traditions of creating folk plays that speak to and include the working classes. We’ve almost lost the once-prevalent open air theatre, where the cheap seats are not intimidated by the 'Grand Circle', 'Upper Circle', and 'Royal Boxes'. Our whole language and architecture of theatre commands hierarchical thinking and upholds exclusivity. We glaze over this as part of the spell cast on us when we’re sat hushed in our pews waiting for the curtain to rise – that undeniable feeling we all get that attending theatre feels special. But scour the theory books and ask any theatregoer why theatre really feels special, and the answer won’t be the upholstery.

Theatre gave me confidence in my strength. As a performer, being able to trust my body, and have others trust it with their truths, empowers me. As I grow into a new stage of my career, seeking paid work and more ambitious auditions, my mixed race identity and queerness come up more often. I’ve been advised to play into it, asked to represent minoritised views at large, even dismissed when I question script portrayals. I’ve also had incredible experiences with Edinburgh directors who have helped me celebrate my identity while allowing me to be more than queer and brown. Increasingly diverse representation on stage and screen gives me hope that I can pursue a career in acting, compared with eighteen-year-old me who had very few role models that looked or lived like me.

So, let’s dream. Let’s envision Scotland if an honest diversity of worldviews were regularly platformed. If we commit to sustained funding opportunities for minoritised creatives beyond early-career platforming, we have a greater pool of mentors to steward future generations, creating possibility for a positive cycle. If we take risks in decolonised programming, we can celebrate the immense contributions the global majority have already made to theatre. Our scripts become less restricted to struggle stories. Minoritised folk can feel like theatre is being made for them. The culture of theatre itself can begin to change, without losing what has always made it special.

It’s 2065, and there’s a little girl in the front row who recently moved to Scotland. She gets that feeling when you recognise something you’ve never been able to articulate, but know immediately upon arrival to be true.