Our Stories podcast: Episode Three

Read the transcript for the third episode of Our Stories, recording during Natasha Thembiso Ruwona's programmed event at David Livingstone Birthplace in late 2022

This is the transcript for episode three of the Our Stories podcast, you can find the transcripts for episodes one, two and four here.

EPISODE 3 - The stories we tell each other and ourselves

CONTENT WARNING

Eilidh Akilade: Before this podcast begins, we wanted to give you a gentle warning - this podcast can be a hard listen at times and includes themes and discussions of trauma, racism, colonisation and more. It’s something you might need to consider before listening.

INTRODUCTION

EA: Whilst storytelling can help us understand others and ourselves, we often have to navigate myths and memories that hold conflicts or truths overtaken by others. BUT…for many understanding their past, their families, their roots - it can be the one thing that brings real connection to ourselves and those around us.

In late 2022, Scottish-Zimbabwean artist and researcher Natasha Thembiso Ruwona programmed an event titled Our Stories Between the Myths and Memories in partnership with The Skinny. Hosted at David Livingstone Birthplace in Blantyre, Natasha brought together a wealth of creative practitioners from the Scottish African diaspora to celebrate their contributions to the creative sector.

Natasha’s aim was to let the project speak to past, present and potential futures that examine Black Scottish history, culture and identity. And why the location? Well, it placed a spotlight on the work that David Livingstone Birthplace are doing as they consider the role of museums within truthful storytelling.

My name is Eilidh Akilade, I am the intersections editor at The Skinny and over this 4-part podcast series brought to you by the magazine in partnership with We Are Here Scotland, you will experience some of the conversations, questions, creativity and reflections that came out of that weekend.

Welcome to Our Stories…

In this, our penultimate episode of the series, we’re looking at one of the reasons why this podcast came together. It’s about the stories we tell each other and ourselves. When Natasha was curating this series they said it would look at reflecting on the stories that David Livingstone Birthplace are telling, the stories artists of the African Scottish diaspora are telling, and how these can act as bridges between people, storytelling then became the overall theme. I am going to look at that in a bit more detail now…

Part 1: Natasha & Clementine

You may remember in our first episode we opened with a brilliant performance from Natasha where they composed a response to David Livingstone Birthplace. As part of that same chapter of the event Natasha was joined by Clementine Burnley who we will meet now.

Clementine is a mother, public storyteller, and community worker. Her short pieces, essays and poetry have appeared in a number of notable publications. She has also been in the final selection for a number of Prizes including the Amsterdam Open Book Prize.

She delivered a presentation as part of the event and called it the Toy Box. She wanted to look at how we tell each other about the present that we're living in, the kind of future that we want to build together, what our stories are, what our roles are in that and what we win and perhaps lose.

I am going to start with highlighting an important excerpt where Clementine talks about maps…

Clementine Burnley: How are the stories told through maps? Because in the end, a map is a fantasy. Most of these maps were made for this era without people ever having been to any of the places they were talking about. And I think the consideration of not making as attachment of fact to image is something which I think I'm only coming to terms with in terms of understanding that the picture, the story the map tells is only as good as the information that's on it.

EA: Accompanying this podcast I am going to include Clementine’s presentation for you to look at but I wanted to try and highlight some of the things that stood out, for me anyway.

Many early maps were based on oral tradition and personal observations, which could be subjective and error-prone, so when it came to colonisation there was an interpretation that was brought back for the Western world which included a lot of myth and also some fantastical but deeply harmful imagery. This was one of the many ways in which colonisers, enslavers, and traders indoctrinated wider society but also garnered support. Storytelling, here, became a tool of white supremacy.

The main focus of Clementine’s presentation was her research into games - board games, computer and video games. But it’s the thread that she weaves and the profound theme that rises from her analysis that makes this something that stayed with me.

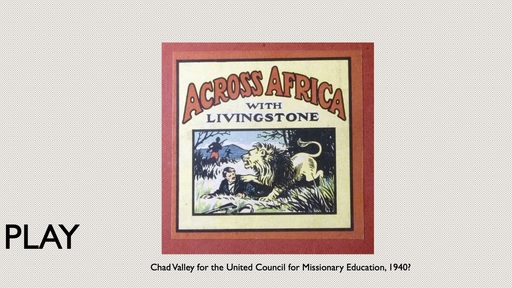

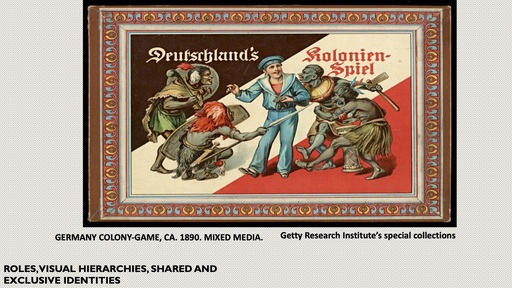

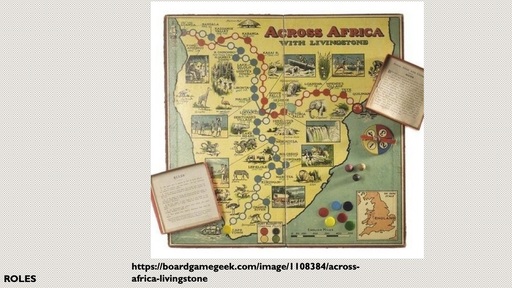

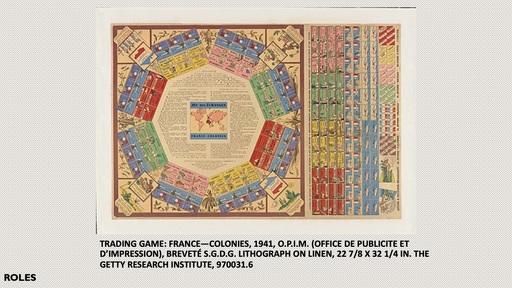

Clementine looked at 5 games inspired by thoughts around colonisation, exploration, adventure and faith, amongst other things: Across Africa with Livingston - a board game from around 1940, Deutschland’s Kolonien-Spiel - a board game from around 1890, Populous by Bullfrog productions release 1989 via Electronic Arts, Black & White from Lionhead Studios released 2001 and also via Electronic Arts, the popular SimCity published by Maxis in 1989.

I will let her explain further, including why she called her presentation the Toy Box…

CB: This is painful, this is traumatic material. I wanted to have an approach to it which didn't traumatise, because I think that there's been enough trauma but also I wanted to be quite serious about it. And how do you play while being serious? Well, you look at how this subject has been um treated by uh the means of games how children are brought into race and to colonialism, into hierarchy. This particular game is from I think from 1940. I'm not entirely sure. And I'm sure that the museum here can tell me because I think that this was an exhibition. I think about National Museum of Scotland that had this and I found it online. In any case, this is a board game. And so you have the classic imagery. Um, I'll go on a little bit quicker so you can see the thing that I wanted to point out is that in terms of the world map, you have a very particular construction of whom is allowed to travel because travellers are different from migrants.

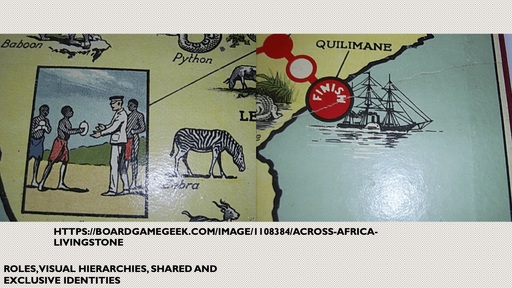

Travellers have adventures and they're allowed to move everywhere. So they can really play and everybody else just is a game piece and they have to stay still where they ah, are. And that's where you have the hard boundary between the native and the missionary. So then in terms of the map, what you do is you have the playing pieces and you go across Africa with Livingston and in the same game, then you end up somewhere. And if you look at the way in which what's on the screen you can see already what roles people have and what story the game itself is trying to tell without ever mentioning um that this is actually education. This is education at a very very early age. Um, so you look at who has clothes and who doesn't have clothes and how they're standing. You can tell by the posture what the hierarchy is, right? So I always wonder how you spend such a long time in a place without making friends. Because I always think that how people relate to each other, who we stand close to and how we look when we look at them. This tells you the relationship without you having the history.

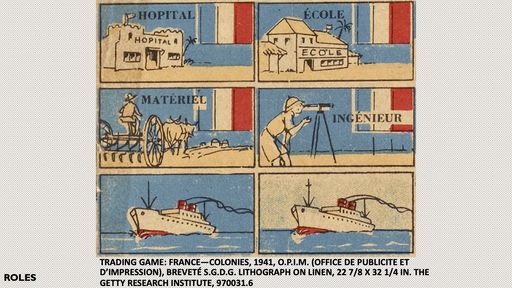

So this is a German colony game, very much for the same purpose and for the same age. And this is a trading game from France. All of this stuff is online to find. So you have the rules and you have the maps are very important. But it's also really important that you have the roles. And so you have to have hospitals and schools and engineers because this is again a way of creating a strict binary between who heals and who is medical. It's also a very strict binary between the modern and the, um, traditional and so you're telling a very particular story.

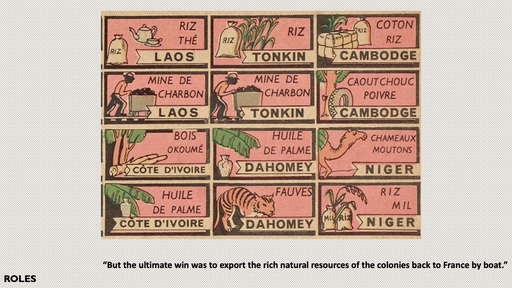

And then um, you have really the purpose of all of this, which is it's material, this is in French, but it's basically rice and tea and the countries from which these goods come. So because these are playing pieces you're teaching children what is the function, what is the economic function between a country existing and uh, what you get from it? So it's like a supermarket game, basically. This country exists because it delivers this and this is the function of this country to the person who is playing the game. And what they have to do is they just have to get as much of this as possible. Right?

It's an interesting education, [inaudible] and into relations between the races. And I imagine everybody plays this game, gets the same education, regardless of what their identity is. Right? So this goes across the boundaries of race and it's really purely about educating people into consumption. And so at the end of all of that, you get trophies, so you get points and uh, then people are sorted into categories and their value to you is the service they deliver to you. And because I was interested in looking at continuities, I really thought about tourism today and whether it's materially changed in terms of who travel and who migrates and who consumes and produces.

Then you have video games. I uh, don't know very much at all about video games, so I talked to my brother-in-law who um, told me about Populous and you can read the description yourself. But you start now to get into a real sort of play role where actually you decompose the world and then you look at it from above and you decide whose where, which is always what you do in a game, but in Populace, you actually become a God.

The next game I am going to look at is Black and White. And so you have the luxury board and they have our world as you know it. So they have islands, they have tribes, they have the villagers, but you also have the village store, which is where you put the goods. You get a creature that you train. So that creature again, is on a pinned pleasure binary. If you're nice to the creature, it performs a particular task. And if it doesn't perform the task, to your satisfaction, you punish it and it's your avatar and this is how you train it. So really what you're talking about there comes in terms of the area that is interesting to you, your area of influence.

So the interesting thing to me about Black and White, uh, is really when they talk about the black and white binary, they mean a good/evil binary. And so the God is good and the God is white. And the way in which the villagers are trained to believe in the God player is by the classic relationship, which I think you can demonstrate when you look at development points. If you look at what happens in development projects, it's very much the same epic. If the God has no followers, then you can attack that God's temple, and you can destroy the temple, because the thing which maintains a God is belief. And it led me to think a little bit about the way that I grew up and how my family educated me in Christianity and what happened to the gods which were no longer worshipped after Christianity.

So I thought that this was a really interesting game, because when you design a video game, you're not designing a video game because you want a brain in history or educate people in hierarchy. You're doing as it's fun, because if it's not fun, it doesn't sell, right? And so I thought it'd be nice to look at something completely unrelated to the museum and to see whether I could find strands there in the modern which had continuities with what was happening in terms of this sort of education.

And then we get to something that a lot of people might recognise. SimCity is quite old, we come to really what happens when you start to apply video game ethics to urban policies. And if you look at the really large data projects, the surveillance data projects, for instance, the one they run in the GANs database in London, it functions very, very similarly, because the original urban simulation, which, uh, SimCity was based on, was used with politicians for them to be while they were campaigning, they also used the simulation to implement their proposed policies. One of the interesting things I thought I'm on the link with SimCity there is an actual video which explains to you what uh, an urban simulation game like SimCity has to do with how you plan where people live. And that's why I decided to call this presentation the Toy Box. Because if you look at a game like that, you are not able to see how the rules have been written which run the game. So it's a black box algorithm, all the algorithms are concealed. But apparently when you play that particular game to win, what you have to do is you have to take out all the schools, you have to take out all the hospitals, you have to take out all the social services and you have to increase the police presence. And when you have a space which is anonymous, in which all of the buildings are exactly the same, you have a population which lives to succeed. Um, you have a very high proportion of the population being police. And at that point, you have to run a successfully that is how to win at SimCity. It is a little bit of a grim, if that is the toy box with which we are playing for the future that we would like to have in a time of climate crisis, I think that we have to start to think a little bit differently.

As a result of a process in which I didn't want particularly to be retraumatised by going into really colonial violence right. Because we are circling all the time around topics which produce sometimes, depending on how you're positioned, not very much emotion in some people and there is high levels of emotion in other people. I didn't want to enter that field taking it too seriously. This is what I love about the approach that you use is how do you deal with this without repeating or reproducing the disconnection in relationships which has happened in the past and continues to happen now. Play begins to cross over with reality, and where it produces interesting questions for the future, for the future that we imagine together, when we imagine a future which is that of care.

EA: Some of the things that jumped out for me from Clementine’s superb presentation and analysis were thoughts surrounding: the difficulty in changing if you are not allowed to be anything else and potentially the conformity around things which perhaps comes not only from ownership but the beliefs taught to others, the psychological differences and ignorance surrounding migration vs travel and adventure. The importance of belief and who buys into this.

The way in which these fundamental beliefs are taught through the disconnection of gaming which is something which entertains but forgets the violation that has influenced it and finally something that I will explore further in our final episode, and as Clementine puts: the future that we imagine together when we imagine a future, which is that of care.

The thread of storytelling continues through all these mediums, through entertainment, belief, faith, and conformity, but what have the costs been and how can we change the narrative? But also, how can we use this to look at the stories we tell ourselves?

Part 2: The Panel

EA: I am going to bring in some new voices now. As part of the event, a number of the creatives taking part in their own commissions gathered together for an informal panel and discussion about their work and their relationship to storytelling and community. Those people were Tomiwa Folorunso who we have already met, spoken word artist Inga Dale who we met in our last episode. Writer, curator, organiser layla-roxanne hill who co-wrote Black Oot Here: Black Lives in Scotland and someone we will hear from more in our final episode. Etienne Kubwabo - filmmaker, writer and creator of popular comic series Beats of War featuring Scotland’s first Black superhero and finally Divine Tessinda, a professional choreographer, dancer, designer and model and one of the owners of 360 Company.

Tomiwa: Obviously, this whole weekend is about storytelling and myth and memories and stories themselves, as well as the storytellers. And I kind of wanted to ask you first. Today we're in a museum. Do you think museums are good storytellers? And that's a big question. I know.

Inga: It's an interesting question and something I've never thought of before, going into a museum and thinking of it as a space that tells stories, but I suppose that it is. But I think it also depends on who's curating, uh, an exhibition, um, and what's the story they're trying to tell. If the curators of the space comes from a certain lived experience, the story that they are going to tell is from their lens or their perception of how they see the world. Perhaps certain exhibitions can tell a story historically, but doesn't really delve deep into the lived experiences of what an artefact is representing. So, for example, if you're in a museum that shows an artefact of a bowl, like from Africa, yeah, it tells you something about it factually, but there's no emotional attachment to it, and there's no link to lived experiences and what that meant to the community. That was using this bowl, for example.

Divine: I think that it definitely depends on who is telling that story because, personally, we go in to see stories, we go in to learn history, we go in to explore and take in new information that perhaps we didn't have before. But it does come down to really who's telling that story and also knowing that everybody just because everybody sees the same buyer doesn't mean everyone's going to describe it the same way.

layla-roxanne: I think as, uh, physical spaces, they can be pretty incredible. We can offer a lot of peace, we can offer a lot of connection as a physical space, but then also who's able to access that space and who feels comfortable being in that space. And I always remember having a conversation with a taxi driver who was born and brought up in Glasgow and had never been to Kelvingrove Museum and said that that space wasn't for him. You just didn't feel comfortable. So I was like, well, what's your interest? It was football. And I said, well, what if there was like an ah, exhibition on that had the focus of your favourite team not going to mention what that team was? He was like, Maybe, but I just wouldn't feel comfortable going into that space. And I know, especially for a lot of Black people, if you're going into a museum, and it's usually a very white space, both in terms of the people that are in there, but also how it looks, and you're maybe seeing like, instruments or items from your country with no real context, that can be quite an isolating experience as well. You feel that people are looking at you, questioning why you're there, what's your interest. But I think also when you go back to the curatorial side of it, it's what histories are kept, what's important, who deem items to be of value, and why and why show them. We know that there are some things that are kept, and they're kept in storage for a very, very long time, and then they're not put out, or they're put out because it becomes quite popular or trendy. Black History Month where we're starting to have a conversation about colonialism. So let's stick that bring all the logic side. But I think also, like, lives and experiences and ideas which offer an alternative vision or an alternative to like, the dominant ideology or the state of co that probably won't be shown because that might give people some radical ideas.

Tomiwa: Yeah, there is something in that inaccessibility of the space. And it just makes me think as well, in a sense, how unnatural it is to kind of be in a museum and to look at all this stuff and taking all this information, but you're not really allowed to touch anything, and you have to be quiet, and you have to follow it in this certain path or the route that the curator has created. And that can be very overwhelming. And just a bit like, why am I here? And maybe not always the best way to engage, I think, as well. To move a little bit away from museums. I'm thinking more so about our stories. You are all creators and practitioners and artists in different forms of storytelling. And I'd really like to hear about why it is, and if you feel it's important, firstly, I suppose, to tell your story or our story, and why we should be telling our stories through art or through creativity.

Etienne: I think telling our stories through art and creativity is like I speak for myself. Uh, it's like keeping the five-year Etienne alive. Because I remember growing up, I’ve always loved stories and are going to a lot of trouble for watching too much TV or reading a lot of comic books, stories have always been part of me, and I've always felt like me living in Africa, coming from Africa, and then coming to Scotland, how can I tell a story that is so original and unique to myself? Because everybody's got different life experiences, and your story might be different from my story. So it was really important for me to go back to the roots of who I am, where I come from, my character, and how can I bring that and be as honest as possible through stories. So, yeah, even that's why even with Beats of War, there are two stories, one that represents where I come from, and, Scotland, which is my new home. So, yeah. Staying true to yourself. Really?

Divine: Yes, stay true to yourself. We tell stories through art because art is life. Art is your day to day things that you experience. Think about the amount of time we all listen to music, right? You might not necessarily always watch a dance video on YouTube or Instagram, but the amount of time you have your earphones on you're listening to someone tell their story. The amount of time you're passing by a street and there's an advertisement on the bus on the wall. The amount of time we're conversing with people. We are living that story as is happening. Knowing that you have your own voice and your own platform to tell your version of your story the way that you want it to be perceived from your own voice, from your own true opinion, and how you perceive and how you see your story even when somebody else has experienced what you've experienced. But the way you both felt about it is still different. Whether people acknowledge it or not, art moves us.

Inga: And we're also experts in our own lived experience, so we need to be able to tell our own stories, because I feel when other people tell our stories, for us, it can become problematic.

layla-roxanne: I think it's also like figuring out the ways in which art and creativity is projected, or how that's also contained as well. And just going back to what we're saying, that there's a creativity and there's an artisticness and all of it, but then a lot of people go, well, I'm not creative. I'm not artistic. That's not, for me, in much the same way about museums. But when you think about how museums are like those silent places. But creativity is not a silent process. It's like our stories are not a silent process. There's creativity in the way that we do our hair. There's creativity in the way that you put a meal together. So, yeah, I think it's just something about in the ways in which our own personal stories, putting together a full album that's creative, that's a cultural experience, like, that's artistic.

Tomiwa: I wanted to follow up, I think, with and I don't even really like using the word audiences all the time, but for audiences, for communities, for culture, earth, for society, what is the power of telling our story? Um okay, is there a power? What is that power?

Inga: When we tell our own stories, it also avoids homogenising an entire group. I think that, um, African people are homogenised in a certain way. Um, and that's also due to movies, I mean, if you watch, um, comedies, right? And they speak about Africa, it's always Africa as a place. And that place has animals and tribes, and that's it. So every time someone asks you about, like, I went to the States and I said, I'm from South Africa. And just the questions that I was asked, how do you not know that there's development in Africa? And there are cities. I don't live in the hut. So if we were able to tell our stories, even through movies, if we had more Black directors and scriptwriters, it will break away that homogenised version of the way people view us.

Etienne: But I think the power story enables us not to forget who you are. And if you forget who you are and who are you as a human being. And I think that's the thing I've always put in my art in writing and creating stuff. How do I have my voice in everything that I'm doing.

EA: I think everyone brought such a unique view to that panel, it prompted a number of further reflections for me including the ongoing subject of museum accessibility. And I think that can be viewed in a binary way at times, whereby people look at the physicalities of access, often in terms of disability. Whilst that is such an important subject, I think we have to remember access in terms of income, race, mental health, sexuality and more. As mentioned during this conversation, the isolation this brings is overwhelming.

Tomiwa’s observations about museums - how things much not be touched, there must be quiet and the direction in which you are pointed to experience a museum - is such a contradiction to many of the African interactions with art and its creativity. The vibrancy, the community, the noise and the lack of conformity is what makes it feel not so much a juxtaposition, that feels like too much of a polite term but more something that drains the core expression of what many of these artefacts and subsequent stories brought.

Heritage is something that brings a lot of pride to people and whether people are mixed heritage, or they have emigrated to Scotland from Africa, there’s a desire to hold onto roots and let them form stories and identities, but there is a need also for people to process their emotions and to make sense of their experiences. The cultural values and perseverance of history is also something I think we need to remember, especially when you have systems at play who dismantle that for personal gain and power.

One of the other many highlights of this conversation for me include Inga’s point about one story not representing the masses and her views around homogenisation which alters a natural structure, and brings a lack of diversity, loss of knowledge and practices that have been important for the survival of certain communities. It can also be viewed as a form of cultural imperialism, in which dominant cultures and values are imposed on others without their consent, that in itself can strip a story of all its worth and destroy what made it so important in the first place.

And as for the power and importance of creativity in storytelling? Well I think layla-roxanne puts it perfectly when they say that creativity within many of our communities is through things we perhaps don’t even realise - when we do our hair, when we make a meal - everyone has creativity in them. I wonder how - or if - we can bring more of that authentic storytelling and creativity into the quiet, still, often conformed places like museums?

Part 3: Tomiwa - Home Part 3

EA: We end this episode with another taste of Tomiwai’s essay which she co-wrote with Hamzah Hussain, "Ghar, Ile, Home" - I think it brings back into focus the bridges we build between our worlds, our timelines and our relationships which all add to our own stories and how powerful they can be.

The feeling of a plane starting its descent over Edinburgh will never get old. It feels safe, feels easy. And for those last few minutes, it feels like it's just me as I stare down below, ticking off the people and places in my mind's eye. My brother, Portabello, Jen, Leith, my mum, New Haven, Liam, Muirhouse, Alice's [inaudible], Hay. Home is arriving into a virtually empty Waverey Station at 11:30p.m. And stepping out onto the bridge, staring up at the Scots Monument as the rain hits my face. Home is culture. Home is comfort. Home is my dad kissing the top of my head, mum squeezing my cheeks before bed and [inaudible] putting his arm around me as we walk through security in Lagos Airport. Home is my cousin shouting my name and the smell of plantain. It's Emily asking me if I want some tea and sitting on the step outside Wildfire with lindsay. Home is riding on the top deck of the number eleven bus at 6:30 am making its way down New Haven Road and watching the sunrise around Arthur's Seat. Home is Kirstin and Alice. And Kirsty and Lexi, too. It's the smell of Olivia's Nona's house and the Omni Centre at the top of Elm Row. It's the M&S food court on a sad day and Victoria Park on a good one. Home is safe and it holds you. It protects you, it loves you and it comforts you.

[OUTRO]

Next time, in our final episode, we explore how we collectively imagine our futures…

In the meantime, if you want to learn more about David Livingstone Birthplace and make up your own mind, they are located in Blantyre and we will provide more information in the show notes to accompany this episode.

CREDITS:

This podcast from The Skinny was presented by me, Eilidh Akilade, produced, recorded and edited by Halina Rifai and is in partnership with We Are Here Scotland. The live recordings were made by Hamish Campbell of Sound Sound. This series was commissioned by David Livingstone Birthplace and was made possible through funding from Museums Galleries Scotland.