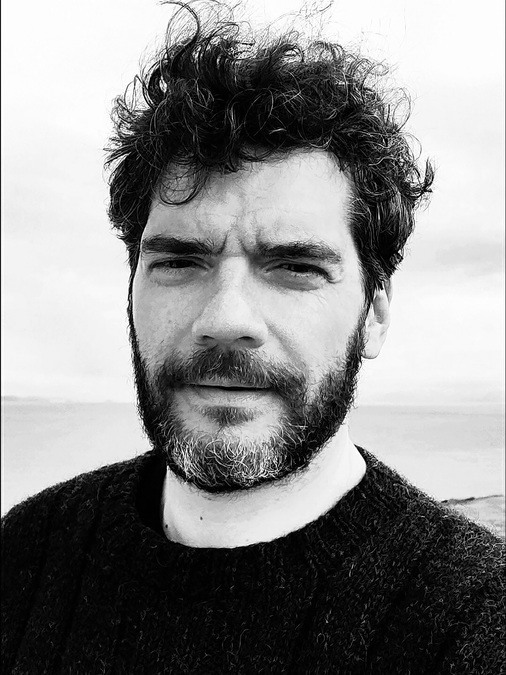

Felipe Bustos Sierra on Everybody to Kenmure Street

The Kenmure Street protest of 2021 saw a community save two of their neighbours from deportation through solidarity and collective action. Felipe Bustos Sierra's film Everybody to Kenmure Street immortalises this special day in Glasgow's history

With two feature films now under his belt, Felipe Bustos Sierra has emerged as one of Scotland’s finest documentarians. The Edinburgh-based Chilean-Belgian filmmaker’s 2018 debut, Nae Pasaran, told the rousing story of how, in 1974, a group of factory workers at East Kilbride’s Rolls-Royce plant refused to do vital repairs on the Hawker Hunter jets that were key to General Pinochet’s bloody military coup in Chile the year prior. Little did they know that their act of solidarity would significantly hamper Pinochet’s air force and that news of their protest would spread to Chilean political prisoners, giving them much-needed solace that people halfway around the world were in their corner. Eight years later, we get his similarly powerful second feature, Everybody to Kenmure Street, and it’s another deeply moving look at ordinary people taking a stand against injustice.

The film chronicles the events of 13 May 2021, when the Home Office attempted a dawn raid on Kenmure Street in Pollokshields, Glasgow. Two of the street’s residents were to be detained and potentially deported, but the raid didn’t go to plan. A headstrong cyclist threw himself under the deportation van, preventing it from speeding off, giving other members of the neighbourhood, one of the most ethnically diverse in Scotland, time to block in the van and send out the eponymous call to arms on WhatsApp groups and social media posts for more people to join the protest. Soon, around 2500 people were lining the street, peacefully holding riot police at bay and chanting for the men’s release. After a tense eight-hour standoff, the unthinkable happened: the police backed down, the Home Office gave in to the protestors’ demands, and the two men were released and free to go.

Bustos Sierra was living in Glasgow at the time, and was at home in nearby Govanhill during the protest. “I heard about it really, really early on,” he tells me. “I got a text from a friend; they were reaching out to try to get people to come.” Nae Pasaran had recently screened on terrestrial television, so he was also receiving lots of DMs from strangers, asking him to spread the word on social media. He did, but despite being only ten minutes away from Kenmure Street, he didn’t venture down there. “I think I had the sense of, not despair, but a sort of hopelessness,” he recalls, “that nothing was going to come out of this.”

He puts this despondency down to a succession of recent setbacks on the left. “This was happening on the back of Black Lives Matter, which had been so big and so global, but it had sort of fizzled out, and no concrete policies came out of it. And then there was the murder of Sarah Everard, where we found out the killer was a police officer, and the vigils in her name were also violently repressed. So I had this sense there was no conscience at work on the other side when it came to these events. I felt, ‘What is this protest gonna achieve?’ That was very much my headspace.”

Despite his scepticism, he kept one eye on the developments on Kenmure Street via social media. To say he was blown away by the direction the protest took would be an understatement. “I felt like, 'I've never experienced that', you know? I've been involved in solidarity movements and student protests throughout my youth. We'd had some victories in the Chile solidarity campaign, but nothing really so immediate, nothing so visceral.”

Everybody to Kenmure Street.

Bustos Sierra was elated by the protest’s success, but he was also kicking himself he didn’t witness it firsthand. “I realised that this was something that I needed to experience,” he tells me, “but I hadn't taken the chance to, despite solidarity really equating to survival for people in Chile. I felt like I'd let down the people who'd given me their solidarity in the past.”

As a filmmaker, there was, of course, one way he could relive that day: make a film about it. Within a few days, he'd made contact with producer Ciara Barry, who also lived around the corner from Kenmure Street, and within the week, the ball was rolling on development. “I wanted to use, I suppose, my skills and those of the people I know around me who would connect with this as well, to see what we could do to really document this event properly, so it goes beyond the headlines and beyond a few soundbites and beyond a few tweets.” His starting point was Facebook, Twitter and Instagram. “Going through social media gave us an idea of, Oh, that person was filming, they're getting that angle, it might be interesting to find their footage," he explains. "Or what's this person doing over there? Who are they talking to? What kind of conversation are they having?” From these clips, the spine of the film began to emerge.

He also wanted to meet those people who attended the protest directly. The UK was still under COVID lockdowns during his initial research, so Bustos Sierra started taking participants on long walks around Queen's Park to get their perspectives on the day. “I wanted to know, why did they go? What was the hope? Where was the hope? And most people said, 'You know, we had no hope.'”

One of those people was the man who threw himself under the van, who’s known in the film simply as 'Van Man'. “Van Man told me he was ‘maybe useful for about 15 minutes,’" recalls Bustos Sierra, "literally just taking up space and buying time for somebody else to get a better idea.” Much of Bustos Sierra's focus is on the mechanics of the protest, which he describes as a "baton relay." “I felt like the whole day was like that, ordinary people who did the best they could. I felt like collecting all these little pockets of storytelling from the witnesses on the street, and putting it together would kind of give a sense that it was something bigger.”

This is roughly the form that Everybody to Kenmure Street takes visually. Working with editor Colin Monie, Bustos Sierra has spliced together the array of amateur footage he’s collected from eyewitnesses to shape a picture of the protest from myriad vantage points. He also filmed a multitude of talking head interviews, allowing the protesters the opportunity to give their thoughtful insights, although several key witnesses were reluctant to deliver their testimony on camera, including Van Man, and the nurse who checked in on Van Man throughout the eight hours he was under the vehicle. Bustos Sierra's ingenious workaround was to hire well-known actors to be their proxy on screen – we'll leave the identities of these famous stand-ins as a delightful surprise.

Felipe Bustos Sierra.

Bustos Sierra's film gets into granular detail of how events transpired on 13 May, but his film also zooms out to look at Glasgow in terms of its residents' long history of public rebellion, from Red Clydeside activism of the 1910s and 20s to the Govanhill Baths’ sit-in in 2001 via the historic rent strikes of 1915 and various battles against Thatcher’s government in the 1980s. The idea to lay out Glasgow’s credentials as a city of dissent came to the director during those early conversations in Queen's Park. “I remember younger people telling me they went down to Kenmure Street because they were furious that nobody had ever done anything like this before," he recalls. "And, I thought, 'Well that's great, because that anger brought you onto the street. But also, people have been doing this in Glasgow, and in the Southside in particular, for centuries.'”

I'm speaking to Bustos Sierra a few days out from him heading to the Sundance Film Festival, where Everybody to Kenmure Street will have its world premiere. He tells me he hopes it will be received as a sort of microcosm of what’s currently happening in US cities like Minneapolis and St Paul. Judging from the rapturous early reviews from critics at Sundance, the film seems to have been embraced in the way he had hoped.

He should have fewer worries about its reception at its UK premiere, as the opening film of Glasgow Film Festival – not least because he thinks half the audience will be people who attended the protest. For those who were part of the throng on Kenmure Street, the experience of watching the film should still prove quite revealing. “Many of the people experienced the protests from their close or their side of the streets," says Bustos Sierra. "I think the film will maybe helpfully show what was happening all over the streets; they'll discover new things.” For everyone else, they’re sure to spot some faces they know on screen. “I think there might be some audience member playing Where's Waldo with some of our footage.”

Near the end of Everybody to Kenmure Street, one of the participants says that experiencing the collective emotions within a protest ‘changes your brain chemistry.’ Bustos Sierra reckons watching a movie communally does something similar. “That feeling [of changes to your brain chemistry] is exactly what going to the cinema has done for me from a really early age,” he says. “I love to see films in a full cinema, because you just get such a rush from the crowd. So yeah, protesting and going to the cinema, there's something that's emotionally quite similar. I hope the audience will get to feel some of that.”

Everybody to Kenmure Street has its UK premiere at Glasgow Film Festival on 25 Feb, with an additional screening on 26 Feb, and is released in the UK on 13 Mar by CONIC