Jaune Quick-To-See Smith: Wilding @ Fruitmarket, Edinburgh

A survey exhibition at Fruitmarket raises vital questions of land stewardship and offers tender insight into the life of the late artist-activist Jaune Quick-to-See Smith

Above Fruitmarket’s stairwell hangs a slim, red canoe, populated by a picture book array of wild animals. An oversized fox smiles knowingly at you, a miniature llama ponders a painting on the opposing wall. The animals’ surreal scale and plasticky sheen evoke nursery toys or cobbled together nativity sets. But the canoe, a strange, floating utopia where predator and prey lose distinction, also evokes Noah’s Ark and its promises of hope and renewal. Titled All my Relations (2025), this tender piece by late artist Jaune Quick-to-See Smith foregrounds her concern with land, nature, and collectivity, and is the star piece of her show Wilding, currently running at Fruitmarket.

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith (1940-2025) was an enrolled member of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Nation. An artist, curator, and political activist, Smith made art to fight for Native American rights, drawing rich inspiration from her lineage, the natural landscape, and the cultures of North America. Smith’s work is characterised by bold expressiveness: there’s a sense that each painting and sculpture is newly finished, that the paint hasn’t fully dried. The exhibition booklet includes this passionate quote from the artist: “My work comes right from a visceral place – deep deep – as though my roots extend beyond the soles of my feet into sacred soils. Can I take those feelings and attach them to the passerby? To my dying breath, and my last tube of burnt sienna I will try.”

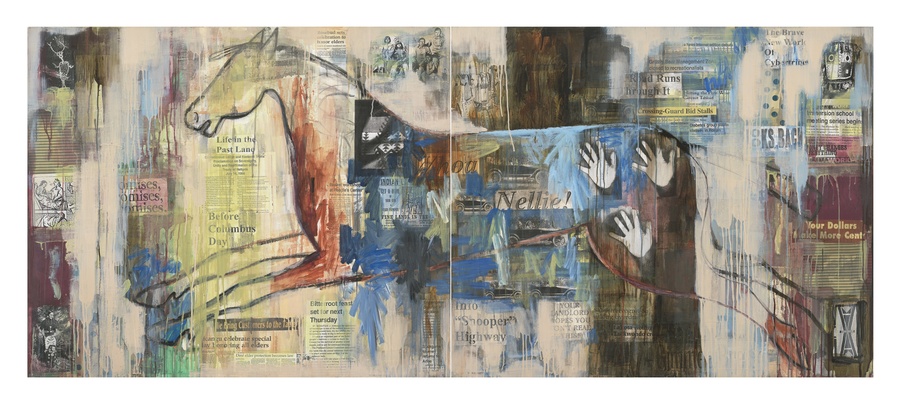

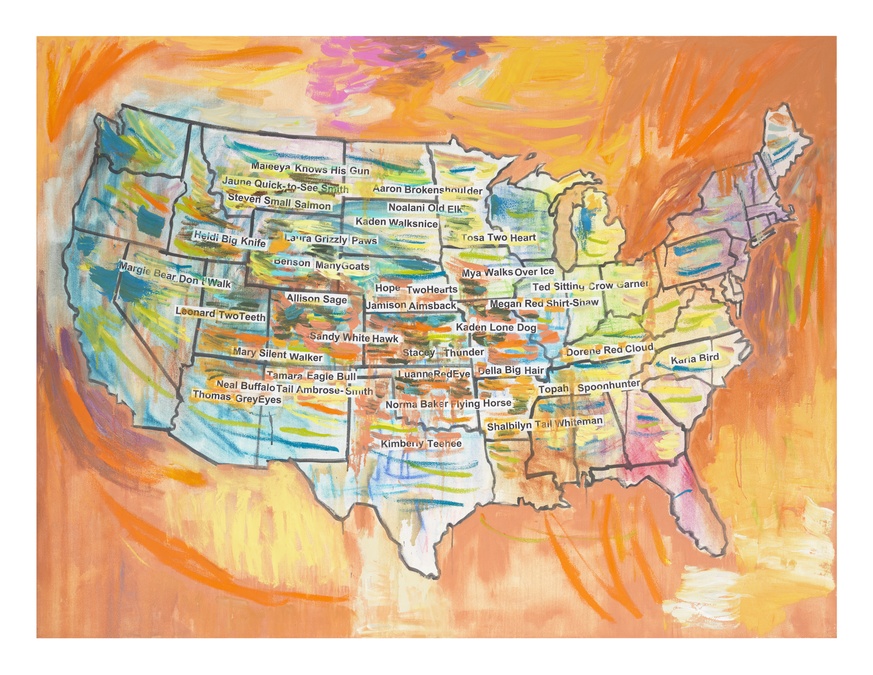

Wilding opens with a series of large collage works that riff on maps of the United States. Each map is outlined in crisp, even black, as though scanned from a student’s workbook, and overtaken with thick brushstrokes whose warm hues evoke desert landscapes. The maps are covered with small, neat labels: in War is War (2023), synonyms for conflict bristle threateningly above different states; American Slang Map (2023) displays a litany of American stereotypes and slurs; while in American Citizens Map (2021), the most brightly coloured of the three pieces, Smith peppers the names of her Native American friends all over the country.

American Citizens Map (2021) by Jaune Quick-to-See Smith

These works show Smith’s gift for blending politics with vivid storytelling. The first two maps are sardonic inversions of the authoritative newspaper infographic: hijacked by roughly applied paint, their nondescript, sans serif labels look foolishly bureaucratic. In American Citizens Map (2021), however, the labelling tactic feels intimate: this piece isn’t just a political statement, it’s also a private map of Smith’s friendships, a contact book, a diary. Short, horizontal dashes flit around the names, giving them movement and buoyancy. I see visitors pause for a long time before these works. These are bold paintings, through which a polyphony of voices – accusing and playful, demanding and gentle – make themselves heard to you.

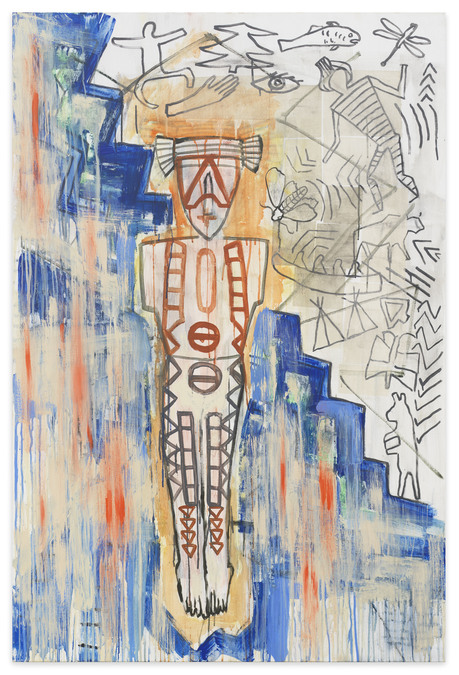

When you ascend to the upper level (with All My Relations (2025) drawing your gaze skywards as you climb the stairs), you’ll be met by a group of sentinels. The Tierra Madre (Mother Earth) series (2024-5) features a group of female ecological activists: Rachel Carson, Robin Wall Kimmerer, Amy Bowers Cordalis, Wilma Mankiller, and Maria Sibylla Merian. Inspired by the Tsagaglalal, ‘she who watches’ over Native land, Smith portrays these women as guardians, framing them in bold patterns and surrounding them with expressive pictographs of plants, animals, and dancing human figures. Despite being faceless and at times even limbless, the women, ensconced in a rich universe of symbols, radiate kindness and warmth. I don’t know how Smith achieves this – it’s testament to her narrative ability. I promise you: you will see these paintings and instantly pick up on benevolence.

Tierra Madre by Jaune Quick-To-See Smith

Wilding touches lightly on Smith’s connection to Scotland, but in a way that raises more questions than provides answers. The guide briefly mentions Smith’s concern with “the politics […] that speak to both Scottish and American contexts,” and the exhibition book says Smith showed a “fierce interest” in the Highland Clearances. However, the exhibition texts don’t really elaborate on this – had I not seen the guide or book, I wouldn’t have read the show in a Scottish context at all.

Nonetheless, Wilding presents a striking series of Smith’s work and raises important questions on ecology and land stewardship. And despite its relatively small scale, Wilding very successfully conveys a sense of Smith’s personal charisma. Perhaps the tenderest part of the show are the interviews with Smith’s son, played on a loop in the upper floor. Reflecting on All My Relations, he says: “It’s more about being together and moving into a space together, and I think that's a great place for us to go.” This line, I think, perfectly encapsulates the ethos of the show.

Jaune Quick-To-See Smith: Wilding, Fruitmarket, Edinburgh, until 1 Feb