Edinburgh College of Art Degree Show 2023: The review

An interest in language and a devotion to craft define Edinburgh College of Art's degree show this year

On the last day of the Edinburgh College of Art (ECA) degree show, there is a palpable frenzy animating the campus. Visitors weave between extraordinary displays – encompassing art, design, music and architecture – in the rush to find a new generation of creatives. As ECA reminds us, this year’s graduates have faced ‘continued challenges across their studies’; majorly impacted by the pandemic, combined with the extortionate increase in art material costs, it is hard to not consider the emotional labour that has fed into the students’ final pieces.

Ammna Sheikh spent 55 hours weaving The Richer A Persian, The Finer His Rugs, a kaleidoscopic display which cleverly illuminates the domineering force of British colonialism on language and visual culture in Pakistan. Across her mesmerising printed paper rugs, the intermedia artist incorporated Persian and Arabic with English and Urdu script (the latter two languages were deemed superior by the British colonialists). In a reclamation of Perso-Arabic script, Sheikh turned to proverbs which, like myth, hold a transformative potential in their ability to convey a cultural story.

The recovery of ‘endangered’ languages was a primary motivator for Tracey McShane’s project, too. In Edinburgh College of Art’s grand hall, McShane’s ginormous scroll imitates a breaking wave crashing into a sea of artistic portfolios. Its shape and volume testify to the extraordinary complexity of Scottish Gaelic; the accompanying statement points out that the language has seventy-three words to describe waves. Up close, the muslin texture of the scroll is delicate and vulnerable, listing 2500 languages on the UNESCO ‘at risk’ register. Like Sheikh, McShane also points out the time taken to create the installation (which runs up to hundreds of hours), conveying a staunch commitment to the preservation of language and culture.

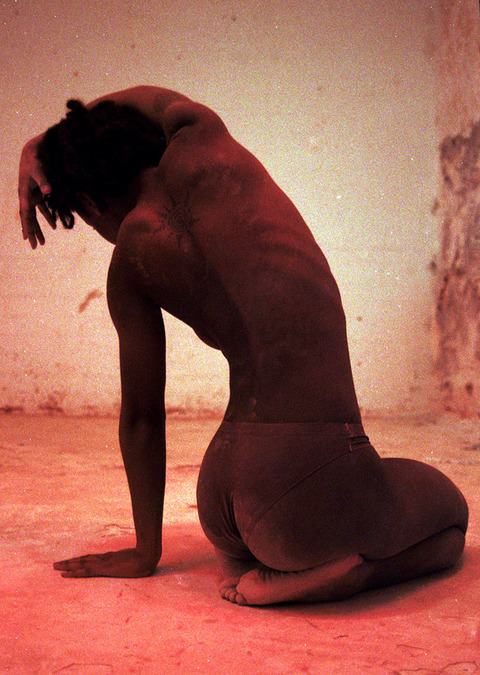

Performance art, which has seemingly taken a back seat in this year’s degree shows, does however feature in Alex Osborn’s self-portraiture. Comprising 120 tiny photographs, Bondage Performance involved the artist wrapping and re-wrapping her own body with red tape while concentrating on the physical sensation. The photographic presentation of this performance sets the tone for Dancing in the Red Room, the pleasure epicentre of Osborn’s art. Inside the cave-like space, which radiates shades of crimson and scarlet, enlarged photographs of women contorting their bodies in accumulated satisfaction hang on the walls. A mutating organ-like soft sculpture sits in the centre, its spewing intestines and guts a reminder of the fragility of the human body.

A welcome relief from the intensity of Dancing in the Red Room, Grace Gershinson’s biomorphic sculptures climb the walls of a room flooded with warm afternoon light, as if they are pining for sunlight. Leaning into abstraction, her sculptures have an organic and obsessive quality; like Yayoi Kusama’s compulsion to paint polka dots, Gershinson has made clusters of repeated, pierced shapes which resemble coral.

Amongst a showcase of Jewellery and Silversmithing graduate collections is Kuruka by Erica Earle-Robertson. Translating as ‘to weave’ in Shona, Earle-Robertson found inspiration from her upbringing in Zimbabwe. Her quad of spectacular baskets could be creatures stolen from the sea, with indigo and turmeric stained yarn, sisal and fibre waywardly shooting from the vessels like human hair. As well as expressing gratitude to the group of women who taught her to weave an Ilala Palm gourd basket, Earle-Robertson has made every effort to emphasise the ‘richness of […] materiality’. Citing the landscape as a ‘critical site’ in her practice, she collects her artistic resources and treats them like precious found objects.

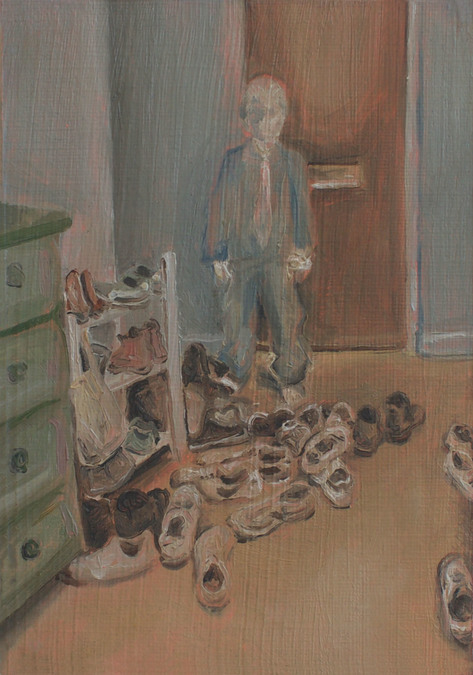

Against the breathtaking backdrop of Edinburgh Castle, a giant doll curiously sits on the window ledge. Crafted by Tegan Chaffer, graduating with a BA in painting, the doll also features on the adjacent wall, inside tiny domestic painted scenes. The miniature paintings capture the mundanity of everyday family life but also the plethora of emotional experiences that are a feature of living with others in close quarters. With its head downcast and blank, the doll’s presence is ominous, perhaps symbolising repressed emotions or unspoken grievances in the context of the family home. In another moment of catharsis, this time a personal exercise on grief, Lauren Maclean took to engraving sonograms on wood to come to terms with her miscarriage.

Comparatively, the push for sustainability and interactivity at ECA was more subtle than witnessed at The Glasgow School of Art's showcase. Instead, as ECA publicly communicates the ‘resilience and hope’ these students have channelled into their art-making, I also see an opportunity to sit with the pain and loss encountered during an educational experience that was deeply entangled with the pandemic.