A Mosaic of Memories: Norman Gilbert at Tramway

We reflect on Norman Gilbert's intimate paintings of his family and the characters of his native Pollokshields

Walking into Tramway is like coming home. A colourful stew of nostalgia and sentimentality, it is hard to not feel warmed and nourished by the current retrospective of Glasgow-based artist Norman Gilbert (1926-2019). Breaking the white cube wall, everyday objects from the Gilbert family home (a stone’s throw away from Tramway) have been incorporated into the wallpapered exhibition space which screams a 1970s aesthetic.

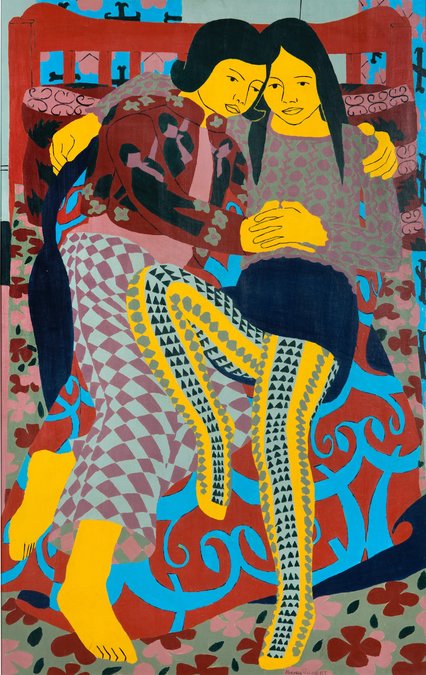

For Bruno Gilbert, the son of the late artist, the exhibition space presents a mosaic of memories. He tells me he was born in a caravan next to a piggery his father was working on and points to a painting which depicts that very caravan. By way of his well-loved moccasins, Bruno can identify himself amongst the portraits of his brothers, Paul, Daniel and Mark. Vibrant textiles, including a tablecloth gifted by a former girlfriend of Bruno’s, lie on a table, demonstrating how his father translated patterns into paintings – often on repeat.

“[My father] is my definition of an artist because he couldn’t not do what he did,” Bruno reflects, radiating with pride. Norman was constantly experimenting, always learning. Deemed “unteachable” at the Glasgow School of Art, Norman carved out his own artistic trajectory. In interviews, when asked which painting is his favourite, it was always “the next one.” Keen to show me how his father’s practice and idiosyncratic style unfolded, Bruno opens a digital archive on his laptop. I’m surprised to see muted naturalistic colours (olive, ochre, dusty pink) dominate the beginning of his oeuvre, incorrectly assuming that he always used a psychedelic palette. The digital archive also demonstrates his transition from shading to flat panels of paint, assembled in sections, like a mosaic.

Quite rightly, Bruno is ambitious about preserving and presenting his father’s legacy. Should an acquisition be made, there are several paintings ringfenced for public collections. Each family member has claimed a painting from Norman’s 70-year career. Bruno tells me how he swapped his original choice (picked for its unique colour palette and use of frozen action) for Totem Pole (1971) which captures an endearingly playful moment with his siblings: one brother sits on Bruno’s shoulders while he holds the youngest in his arms. It’s doubly special because in the background of Totem Pole hangs another portrait of Bruno at a younger age playing the guitar, referencing a painting Norman made in 1963. As anticipated, posing for his father’s portraits as a young boy was not always Bruno’s, nor his brothers’, favourite thing to do. “Especially because he made us wear dresses and pose as girls,” he laughs. His father painted “whoever he could get his hands on” – including the Turner Prize-winning artist Susan Philipsz.

Norman’s portraits were not always made from life. Pocketing snippets of inspiration from his everyday movements, he sometimes relocated passers-by (aka, potential portraiture subjects) into the domestic scenes of his canvas. Bruno shows me how this trick is perhaps most obvious in Plants, Patterns and People (1965), which depicts three women sitting in a row in a living room and staring absent-mindedly into the distance. That they are fully clothed in entrancing 60s attire – coats, gloves, headscarves, and all – is probably the biggest clue; Norman spotted them riding the Glasgow subway.

Towards the end of Norman’s life, the number of potential models frequenting his home and studio depleted, and the number of still lives he produced therefore increased. I’m guided to the last painting he made, Plants, Patchwork and Two Green Chairs (2019). The absence of people in these later still lives only emphasises how sociable their home was, but it also communicates the deep grief carved out by the passing of Pat, Bruno’s mother, and the love of Norman’s life. I am moved by all the anecdotes that Bruno shares with me, but especially by this one: “my father painted three portraits of my mother in the three years before her death and three corresponding empty ‘chair’ subjects […] after her death; each ‘chair’ subject references the corresponding portrait of Pat in its composition.”

There’s a worn wooden box in my parents' house, filled to the brim with photo albums of mine and my sibling’s coming-of-age stories. Standing in Tramway, I get the same tugging feeling in the pit of my stomach when that wooden box is opened, and the photo albums come out to play. I should really visit home soon.

Norman Gilbert, Tramway, Glasgow, until 5 Feb 2023